The Sinclair ZX Spectrum Keyboard

When I was 12 years old, I got sight of an actual computer. One day at my cousins' house, set on a table and wired up to their TV was a small, black rectangle. They were pressing keys on it to play games (Schizoids and Ant Attack I remember). I was curious - the games looked more interesting than the simple arcade games I played on my Atari console. I got closer and peered over and saw the keyboard and it changed my life. Here's what I saw:

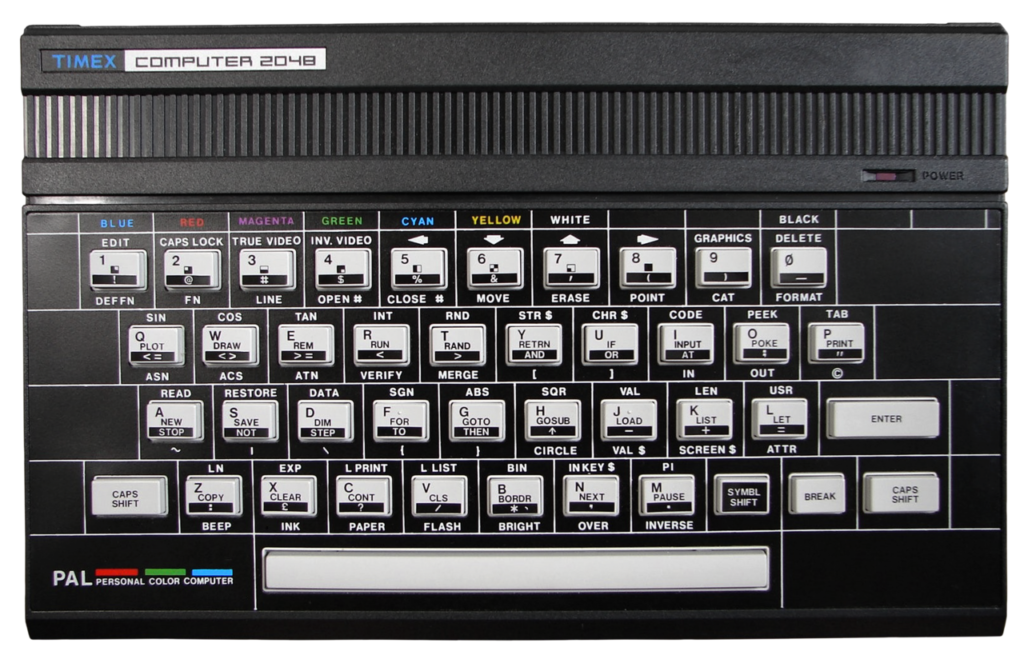

This was a 16K Sinclair ZX Spectrum. What on earth did all those words and symbols mean? It looked like it was made by aliens to control a spaceship.

For playing games, the keyboard was mostly left untouched: Q was up, A was down, O was left and P was right. I later heard that you could use the rest of the keyboard for "programming". What was that? I had to know more. But this was the early 1980s and there was no way for me to find out. The library had nothing. There was nothing on TV yet. School - forget it. Parents - not a chance.

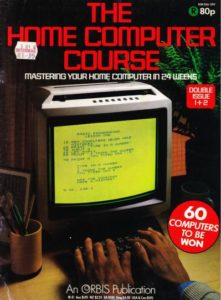

I had a paper-round and about that time, a new weekly magazine was launched:

I bought a copy every Saturday (⅕th of my weekly wage) and read every word. In the first issue, they started a "learn BASIC programming" course and I followed along. It was all very strange: variables and loops. But I got the gist of it and started writing out simple programs in a notebook, ready in case I ever got a computer of my own.

The home computer market was exploding in the UK. Only a couple of years earlier, the machines had monochrome displays and 1K of memory. Now they had fifty times more memory, colourful graphics and sound effects. There were suddenly dozens of computers with similar features to the Spectrum and the Home Computer Course reviewed one in depth each week.

In most cases, the keyboard was an integral part of the computer, but they all had very dull keyboards compared to the Spectrum. The Commodore ones for example (C64 and VIC20) looked like this:

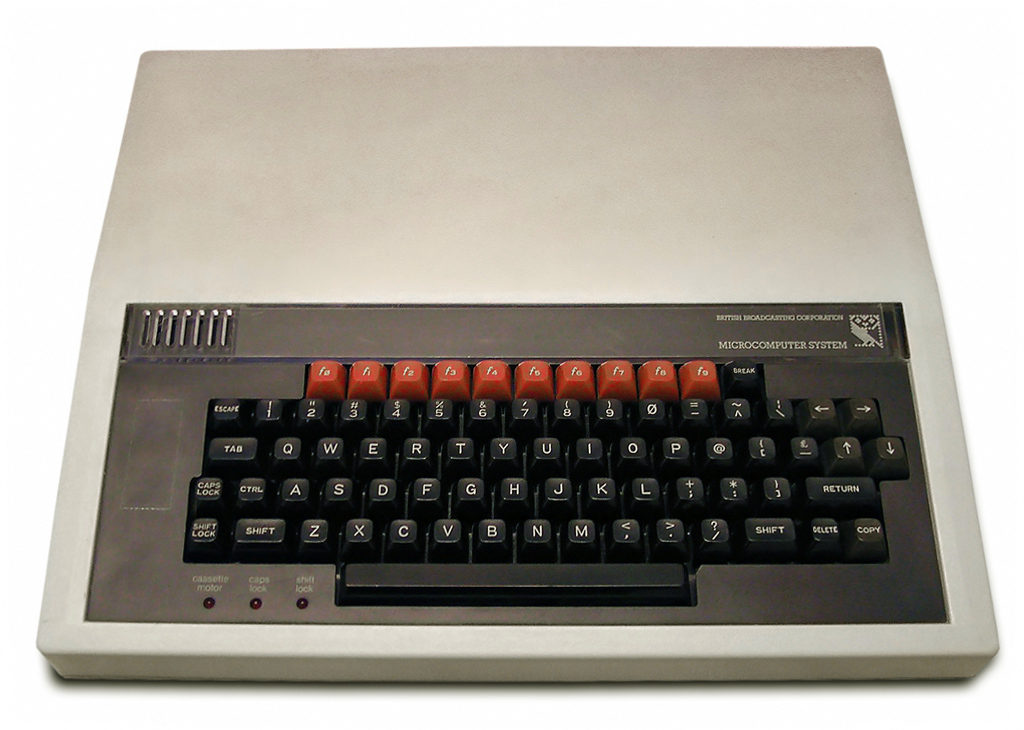

And the (much more expensive) BBC micro looked like this:

They had some weird squiggles like * ~ and # but the Spectrum had those in addition to all the other alien voodoo.

With hindsight, there was a British class thing going on between the families who owned Spectrums and those who owned BBC machines - but that's for another blog post. As is the effect that Thatcherite policies via entrepreneurs like Clive Sinclair had on people like me.

The ZX Spectrum keyboard was very special. The QWERTY layout was based on a typewriter, although the space key was tucked away in the bottom corner: this was not designed for typists. It had rows of small, soft keys - each one a multifaceted jewel packed with powerful incantations. Often ridiculed for its rubberiness, not many commented on the multilayered design. Most of the keys had 6 different functions. The H key for example:

- at the start of a program line would give the

GOSUBkeyword - elsewhere would give the letter 'h'

- with caps shift would give the uppercase letter 'H'

- in extended mode would give the

SQRkeyword - in extended mode with shift would give the

CIRCLEkeyword - with symbol shift would give the

^symbol

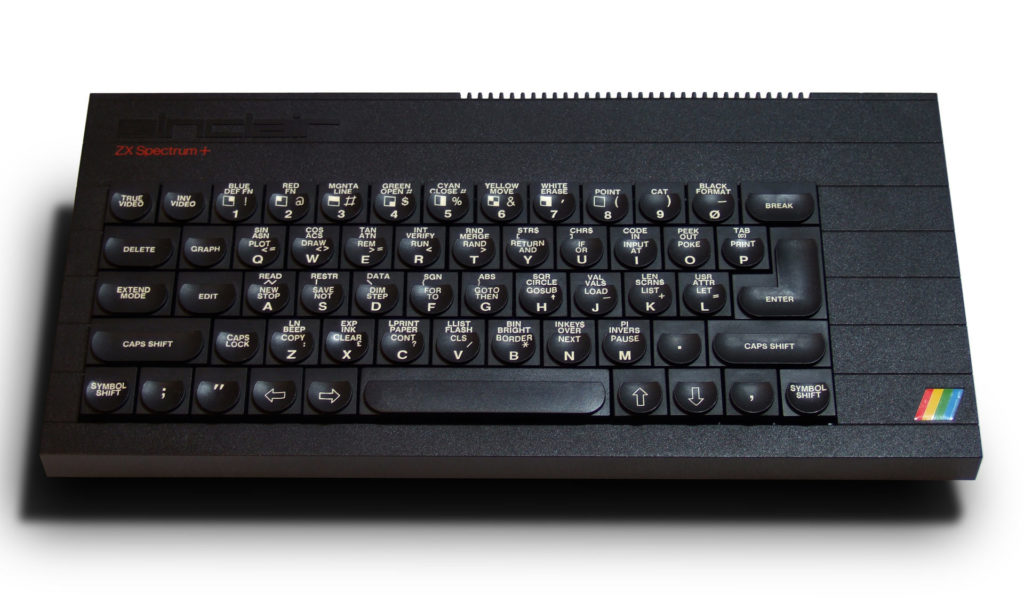

My parents knew I wanted a computer, but I wasn't expecting to get one. Then the following Christmas I received a ZX Spectrum+. This had 48K of memory and had an updated keyboard:

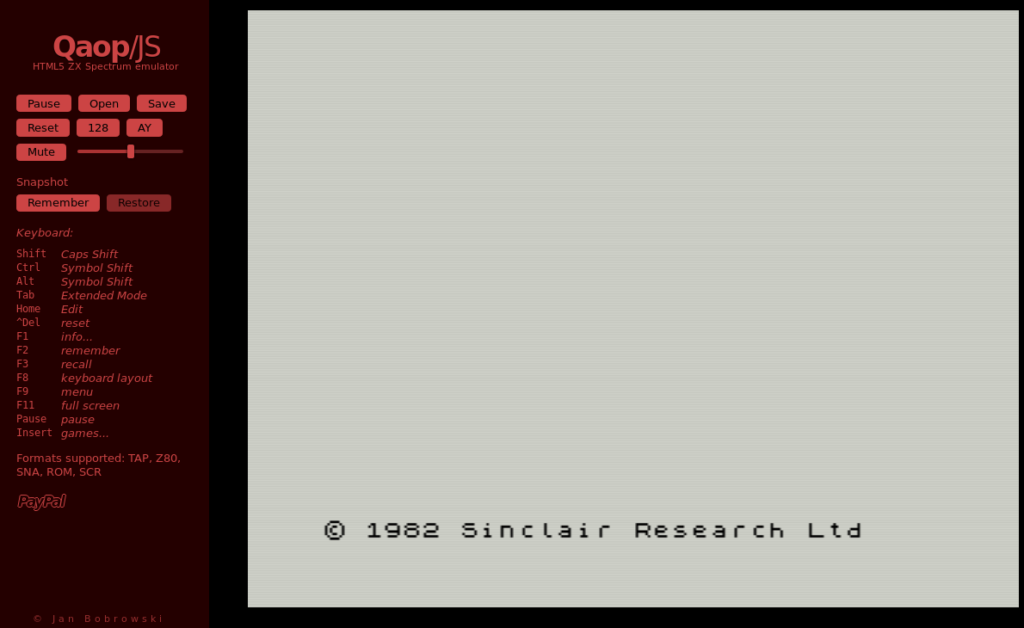

This keyboard was in a more sober black and white and, at first glance, not as bejewelled but all the mysterious markings were still there. When it was switched on it gave a blank screen with a message at the bottom:

© 1982 Sinclair Research LtdPressing a key gave a flashing cursor:

Nothing else; just a throbbing K. For a 13 year old this was very intriguing. An invitation to work out how to talk to the machine.

There was a line editor. To program in Sinclair BASIC you typed a line number to specify the sequence and then pressed a key to give the keyword and followed it by variables, literals and possibly more keywords.

The one-key one-keyword system had several advantages. First, it saved memory. With only a few kilobytes available, every byte counted. Storing each token as a single byte saved lots of space. For example, 1 byte for GOSUB instead of 6 for G, O, S, U, B, plus a space. It also meant the parser could be smaller: no need to check for accurate spelling or the case of "GOSUB" - it was already tokenised. A side-effect of this was that the user had less typing to do and had less chance for typing errors. But I think a crucial side-effect was that all the keywords were printed on the keys. Many of these are familiar words almost forty years later, but back then they were magical words. Words such as DATA, BREAK, GOSUB, ENTER, POKE and INPUT.

As my programming reached the next level, using an actual computer, I began to use more and more of those words and symbols. I even learnt of two new colours: Cyan and Magenta. A few of the keywords were rarely needed and some I would never use because they were for controlling disk drives (CAT, FORMAT) and I only had cassette tape for storage. But some remained unknown, even after trying to read the manual entries and testing them out (they mostly gave syntax errors or strange numbers). These turned out to be the mathematical functions but I couldn't grasp why they were there - maths for me at the time was nothing more than long division and fractions.

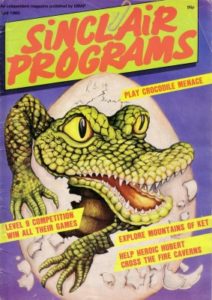

I mostly tried to program games. Starting with laboriously typing in program listings from computer magazines such as Sinclair Programs. This was the first one I bought:

I drew inspiration from many commercial games. A few of my favourite ones were:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e.g. The Colour of Magic |

|

These were all the more enjoyable for having to wait several minutes for them to load:

I should admit that I paid for none of the early games - they were swapped in the playground and copied tape-to-tape.

The manuals for the Spectrum were excellent. I never mastered the Z80 machine language but developed a variety of BASIC programs, all stored on cassette tape. I don't know what people thought I was doing on it all day - they never asked. Some of the types of things I was developing:

- platform games (mostly trying to copy David Jones's work - Spellbound especially)

- platform game room editors

- football and tennis games (mostly trying to copy Jon Ritman's Match Day)

- space flight games (turn-based and simulators)

- graphics drawing programs (tools for creating game assets)

- font creating programs

- teletext systems

- word processors

- programming languages

- database programs

- weather maps

- connect 4 (with the computer as an opponent)

- assemblers

- text adventure games (which smelt of Artificial Intelligence in many ways)

- text adventure game builders (like the Quill)

- text and graphics adventure games (based on one or two screenshots I'd seen of Ultima)

I spent a lot of time trying to work around the limitations of the machine, for example trying get more than 32 characters on a line, like Tasword managed to do:

I learned how to convert between binary and decimal, for creating graphical characters on an 8 by 8 grid. I made re-usable templates covered in cellophane.

Some of my projects failed because I was missing some key knowledge. Any time I wanted to do a physical simulation, such as a pool table or give a 3D perspective, I would be stumped. For example, I really wanted to write a flight simulator and needed to draw a false horizon instrument.

I could draw a circle for the outline using the CIRCLE command. And I could draw a horizon line from one point to another but as the line tilted, its ends would go outside the circle. How could I make the line ends move to fit inside the circle? I tried a few obvious things like shortening it by a pixel for each tilt step but that cut the corners and gave a diagonal sweep inside the circle. I was stuck. I didn't know what to ask, let alone know anyone who could help.

It was only many years later, long after secondary school even, that I realised some of those inscrutable keywords would have helped:

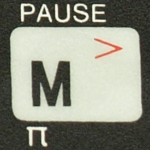

The SIN, COS and TAN functions (and their inverses, ASN, ACS and ATN) and the PI constant (which would have been even more intriguing had they put the π symbol on there - the earlier ZX81 had it):

These functions would have solved many of my problems. How was the teaching of trigonometry at school so dull that I never linked any of it with my passionate interests? It was presented with no contextual or historical introduction and simply shown as a way to find missing parts of triangles with the sole purpose of answering exam questions (which I did well at, but truly understood very little). I am still amazed by how much of the maths education I received managed to completely miss my innate interest in the subject. It was all made so matter-of-fact and detached and never something to be understood or marvelled at. Here's how it should be done:

Despite people telling me to "get outside more instead of staring at a screen", all my early attempts to emulate the programs I liked would come in handy when I later (accidentally) did a degree in Computer Science. There we'd come across similar problems and I'd discover that someone in the 1960s had already thought about it and solved it. Things like how to draw a straight line on a bitmapped screen, how to project a 3D model onto a flat screen, how to parse a language and how to have a natural language conversation with a computer about facts. Having the time to think about these problems in isolation made them all the more enjoyable to study later. I'm still studying them today.

Now I'd like to contrast having a machine like the Spectrum as a child against a couple of alternatives: one co-temporary with the Spectrum, and one more recent.

To play games in most other countries in the 1980s you would most likely have used a home console, for example, the Atari 2600

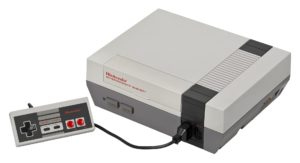

Or the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES):

These had no keyboards, just joysticks, and no way of creating your own games. A whole generation of would-be programmers was left waggling.

The Spectrum was released in the US as a Timex, but I don't think it did so well:

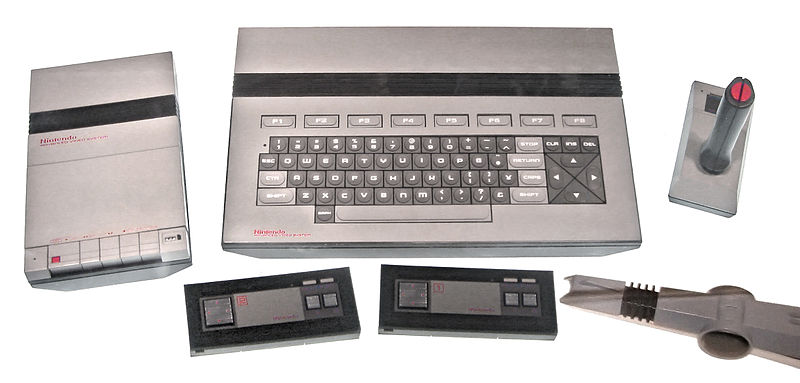

The NES was originally going to be more like this:

What a difference that would have made.

Today, younger generations are faced with something equally as closed:

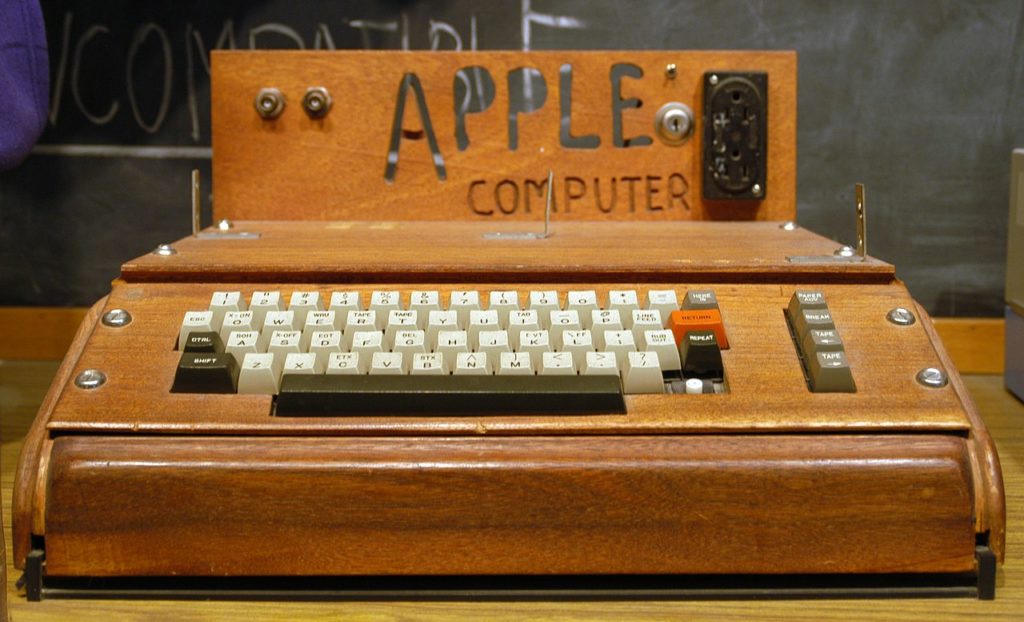

Introducing iPads into primary schools to teach kids "computing" is probably not going to have the desired effect. Ironic coming from the company who created this:

Some lessons I think:

- A flashing cursor (blank page) with some enticing pointers to make your own things can be a better invitation to learn than a set of menus, or a step by step tutorial or a pre-built app.

- Don't over-simplify something by hiding things: lead them on with intrigue and enigmatic references. Keep the most advanced things visible and accessible. This worked for me another time with Chemistry lessons. They were fairly dull (again a subject I was fascinated with before school) but there was one thing that a teacher said to us which made me consider doing an advanced course. It was a bombshell to me along the lines of "of course this [the Bohr model of the atom] is all wrong, but I can't explain why here - you'll need to study A-level to see why.")

- We've grown used to it over a couple of decades but the ability to find out how to do anything on the internet is truly amazing and removes so many barriers for so many people.

That Cambrian explosion of home computers will live forever. They're emulated in software now and so are reincarnated in every new wave of machines. There's even a Spectrum one as an easter-egg in a well-known TV broadcaster's Film Scheduling system - ahem.

Here's just one ZX Spectrum emulator that runs in a web browser:

Unfortunately the keyboards we have now are all the same, unadorned by gems, but their interconnectedness means we can share and find our own jewels.